The Effect of Family–Work and Work–Family Conflict on Call Center Workers’ Emotional Exhaustion With Person–Job Fit as Antecedent*

Efecto del conflicto familia-trabajo y trabajo-familia en el agotamiento emocional de los trabajadores en centros de llamadas considerando la compatibilidad persona-trabajo como antecedente

Received: 13 September 2019

Accepted: 16 November 2019

Abstract

In accordance with the government’s regulations in Indonesia, all financial services institutions are obliged to implement a customer complaint handling mechanism, which has contributed to the rapid growth of the call center industry. As a benchmark for managing service quality, call center workers are required to always keep their emotions stable despite the continuous pressures and unpleasant responses from customers. For this reason, working at call centers is now considered a job with a high emotional burden. Few studies have specifically examined the level of emotional exhaustion among call center workers in Indonesia. Therefore, this work aims to investigate the effect of family–work and work–family conflict on such workers’ emotional exhaustion, with person–job fit as antecedent. For this purpose, we collected data from 154 questionnaires completed by call center workers at financial services institutions in Indonesia. We analyze the relationship among the variables under study using structural equation modeling (SEM). The results show that the level of compatibility between employees’ and their job reduces both family–work and work–family conflict. In terms of work–family conflict, call center workers will feel emotionally exhausted only when faced with a dilemma between work and family responsibilities. The call centers’ management should thus create a family-friendly work environment to ensure excellent care for employees.

Keywords: call center worker, emotional exhaustion, family–work conflict, work–family conflict, person–job fit.

JEL Classification: J24, D23, D74, G21.

Resumen

De acuerdo con las normas establecidas por el gobierno de Indonesia, todas las instituciones financieras están obligadas a contar con un mecanismo de gestión de quejas y reclamos, lo que ha generado un rápido crecimiento de la industria de los centros de llamadas. Como punto de referencia para gestionar la calidad del servicio, los trabajadores en dichos centros deben mantener siempre estables sus emociones a pesar de las continuas presiones y las respuestas desagradables por parte de los clientes. Esto ha llevado a que trabajar en centro de llamadas se considere como un trabajo con una alta carga emocional. Hasta ahora, pocos estudios han examinado específicamente el nivel de agotamiento emocional entre los trabajadores en centros de llamadas en Indonesia. Por consiguiente, este estudio pretende investigar el efecto del conflicto familia-trabajo y trabajo-familia en el agotamiento emocional de dichos trabajadores, considerando la compatibilidad persona-trabajo como antecedente. Para este propósito, recolectamos datos de trabajadores en centros de llamadas en instituciones financieras en Indonesia. Usamos modelos de ecuaciones estructurales para analizar la relación entre las variables estudiadas. Los resultados muestran que el nivel de afinidad entre dichos trabajadores y su trabajo reduce los conflictos familia-trabajo y trabajo-familia. En términos de conflicto trabajo-familia, los trabajadores en centros de llamadas se sentirán emocionalmente agotados solo cuando se enfrenten a un dilema entre su trabajo y sus responsabilidades familiares. Por lo tanto, el área de gerencia de dichos centros debería crear un ambiente de trabajo familiar para garantizar que el servicio al trabajador sea excelente.

Palabras clave: trabajador en centros de llamadas, agotamiento emocional, conflicto familia-trabajo, conflicto trabajo-familia, compatibilidad persona-trabajo.

Clasificación JEL: J24, D23, D74, G21.

1. INTRODUCTION

The financial services industry plays an important role in the Indonesian economy. This sector helps the government to reduce poverty and inequality by providing credit options to individuals (

Call center operations are currently a vital part in customer service because consumers’ perceptions of companies are primarily determined by the quality of customer interactions when submitting complaints

Such high pressure might also cause call center workers—an example of frontline employees (FLEs)—to undergo work–family conflict and family–work conflict. A previous study by Karatepe (2013) revealed that work–family conflict and family–work conflict are two predictors of emotional exhaustion experienced by FLEs. Therefore, in order for FLEs to find a balance between work (and family) and family (and work) and person–job fit, their abilities and the demands of the job must be aligned (

Additionally, some studies have discussed the influence of internal work factors (stress, task autonomy, and attitude) on the level of emotional exhaustion among call center workers (

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Emotional exhaustion

According to

Work–family conflict and family–work conflict

Furthermore,

Inter-role conflict is further defined by

A study by

For this study, the definition of “family” (in the Indonesian context) was taken from the Indonesian Marital Law No. 1/1974, which refers to family as an entity of communication and interaction between all parties in fulfilling their roles, such as those of a spouse, a parent with their children, or siblings (

Person–job fit

Person–job fit is a form of person–environment fit. It is defined as the capacity of employees to find congruence between their abilities and the demands of the work they perform (demands–abilities fit) or between their desires and the attributes of their job (needs–supplies fit) (

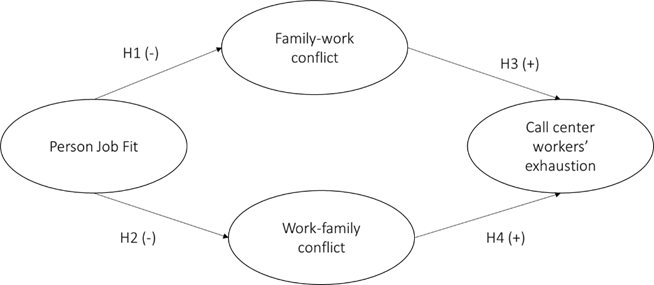

Hypotheses and research model

As explained earlier, the concept of person–job fit proposed by

The study by

Another work by

H1: Person–job fit is negatively related to Family–Work Conflict (FWC).

H2: Person–job fit is negatively related to Work–Family Conflict (WFC).

Moreover,

Besides showing that both family–work conflict and work–family conflict can drain employees' energy and resources,

Another study by

A research conducted by

H3: Family–work conflict is positively related to emotional exhaustion.

H4: Work–family conflict is positively related to emotional exhaustion.

Furthermore, Figure 1 below shows the research model that being explained above.

Figura 1. Modelo de investigación

Source: Created by authors.

3. METHOD

Other studies that indirectly analyze the utility of disclosing accounting information, such as the present o

Sample and procedure

This empirical study was conducted with call center workers from financial institutions (banks and insurance firms) in Jakarta, Indonesia. We chose this city because most call centers in said country are based in Jakarta—the center of business and economy in Indonesia (

Questionnaires were distributed ensuring confidentiality and anonymity. Some questions requested information about the demographic characteristics of the respondents (e.g., gender, age, marital status, number of children), and some others were developed to measure the research variables: person–job fit, family–work conflict, work–family conflict, and emotional exhaustion.

Of the 190 questionnaires distributed to the Call Center Officers (CCOs), only 154 or 81.1 % could be further processed because some respondents did not meet the inclusion criteria.

In terms of demographic characteristics, 87 respondents (56 %) were women, and the rest were men. As for age, 126 respondents (82 %) were 24–26 years old; 17 (11 %), 21–23 years old; and the remaining, 27–30 years old. The working tenure of 118 respondents (77 %) was 1–2 years, and that of the rest, 3–5 years. A total of 82 respondents (53 %) were single, and the remaining were married. Finally, 107 respondents (69 %) reported not to have children; 43 (28 %), 1–2 children; and the rest, 4 children.

Measurement items

For all constructs in this study, we employed scales that have been applied in previous studies. For instance, person–job fit was measured using three-item scales based on the study by

Data analysis

We analyzed the data via Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). We tested the measurement and structural models following a two-step approach (

We conducted the Goodness-Of-Fit (GOF) test with the results of the chi-square (χ2) statistic, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Normed Fit Index (NFI). A model is considered to be a good fit if its chi-square to degree-of-freedom ratio is 3:1 or less, its RMSEA and SRMR are below 0.8, and its CFI and NFI are equal to 0.95 or higher (

4. RESULTS

Results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Based on the results of the CFA, some items were reduced because they had a loading factor below 0. 50 (

The five model fit factors showed good results (χ2 = 190.39, df = 97, χ2/df = 1.96; CFI = 0.95; NFI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.079; SRMR = 0.087). All questions in this study had a loading factor above 0.50 (

Tabla 1. Validez y confiabilidad de los elementos/indicadores/instrumentos de medición

| Latent variable | Indicator | Standardized loading factor | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

| Person–Job Fit | PJF1: My skills and abilities are very compatible with the demands of my job. | 0.86 | 0.815 | 0.604 | |

| PJF2: My personality is very compatible with the requirements of my job. | 0.88 | ||||

| PJF3: There is a good fit between my job and myself. | 0.55 | ||||

| Work–Family Conflict | WFC1: The demands of my job interfere with my family life. | 0.79 | 0.824 | 0.542 | |

| WFC2: My working hours make it difficult for me to fulfill my responsibilities as a family member. | 0.62 | ||||

| WFC3: I am unable to fulfill my responsibilities at home due to the demands of my job. | 0.73 | ||||

| WFC5: I usually have to cancel my attendance to family events due to the demands of my job. | 0.79 | ||||

| Family–Work Conflict | FWC1: The demands of my family or partner interfere with my work-related activities. | 0.77 | 0.805 | 0.509 | |

| FWC2: I sometimes have to leave my work because of family matters. | 0.63 | ||||

| FWC3: The requests of my family or partner interfere my work-related activities . | 0.76 | ||||

| FWC4: Some family matters interfere with my job responsibilities, such as starting to work on time, completing daily tasks, and working overtime. | 0.68 | ||||

| Emotional Exhaustion | EE1: My job makes me feel emotionally exhausted. | 0.50 | 0.841 | 0.527 | |

| EE2: I always feel tired when I wake up in the morning because I have to go back to work. | 0.89 | ||||

| EE3: Working all day long makes me feel very tired. | 0.57 | ||||

| EE4: I feel frustrated with my work. | 0.91 | ||||

| EE5: I feel like on the edge. | 0.67 | ||||

Table 2 shows the correlation matrix, along with the mean and standard deviation of each construct used in this study. As for the demographic variables, working tenure shows a significant negative correlation with emotional exhaustion.

Tabla 2. Resumen de estadísticas y correlaciones de las variables observadas

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| 1 | Person–Job Fit | - | |||||||

| 2 | Work–Family Conflict | -0.627** | - | ||||||

| 3 | Family–Work Conflict | -0.462** | 0.737** | - | |||||

| 4 | Emotional Exhaustion | -0.072** | 0.253** | 0.216** | - | ||||

| 5 | Gender | 0.014 | -0.060 | -0.062 | 0.022 | - | |||

| 6 | Marital Status | -0.080 | 0.040 | -0.006 | 0.060 | -0.009 | - | ||

| 7 | No. of Children | 0.146 | -0.098 | -0.032 | 0.062 | 0.005 | -0.676** | - | |

| 8 | Working Tenure | -0.083 | -0.051 | -0.075 | -0.206* | -0.103 | -0.251** | -0.178* | - |

| Mean | 4.78 | 4.35 | 4.30 | 4.36 | 1.56 | 1.53 | 1.33 | 1.23 | |

| Standard Deviation | 1.53 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.42 |

Note: The composite scores of each construct were calculated by averaging the respective item scores. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 (one-tailed test)..

Results of the structural model test

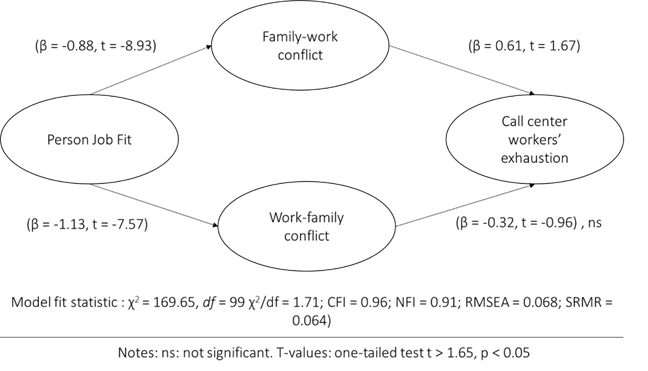

Based on Figure 2 the structural model test yielded good results (χ2 = 169.65, df = 99, χ2/df = 1.71; CFI = 0.96; NFI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.068; SRMR = 0.064). According to such results, person–job fit has a negative impact on both family–work conflict (β = -0.88, t = -8.93) and work–family conflict (β = -1.33, t = -7.57), which supports hypotheses 1 and 2. Additionally, only family–work conflict shows a positive impact on emotional exhaustion (β = 0.61, t = 1.67), while work–family conflict has no effect on emotional exhaustion among call center workers (β = -0.32, t = -0.96).

Figura 2. Resultados de la prueba del modelo estructural

Source: Authors’ elaboration (2019).

5. DISCUSSION

Analysis of the research findings and their theoretical contribution

This study had two purposes. First, it aimed to examine the influence of person–job fit (as one of the individual stressors of role conflict) on call center workers in terms of both family–work conflict and work–family conflict. Second, it sought to determine whether role conflict (family–work conflict and work–family conflict) experienced by call center workers and emotional exhaustion while working are correlated. To analyze the relationship between the variables under study, questionnaires were distributed among call center workers in the financial services industry (banks and insurance companies) in Indonesia. This research yielded several interesting findings.

For instance, our results indicate that person–job fit negatively affects role conflict among call center workers (a type of FLEs). In other words, from the demand angle, the more appropriate their level of skills, knowledge, and abilities to perform their work duties, the less likely they will experience role conflict (family–work conflict and work–family conflict). From the supply angle, if call center workers perceive that their job is compatible or in line with their own personality, they will feel more energetic and comfortable in carrying out their work routines (

Moreover, we only found a relationship between family–work conflict and emotional exhaustion among call center workers. This is consistent with the findings of

Call center workers experience family–work conflict in multiple forms. According to

Work–family conflict was proven not to have a significant effect on the emotional exhaustion experienced by call center workers. Even though this contradicts the results reported by previous studies (

Future research

Further studies should consider several aspects. First, this study did not take into account gender (

Managerial implication

The results of this study have several managerial implications. First, the level of compatibility between individuals (both in terms of personality and skills) and their job (or person–job fit) can prevent role conflict (family–work conflict and work–family conflict) among call center workers in the financial services industry. Therefore, to provide a quality customer service, call center managers (in the financial industry) must assess candidates’ personality and skills during the selection process. Otherwise, they will experience difficulties regarding employee retention (

Second, since family–work conflict plays an important role in emotional exhaustion among call center workers, companies need to create a family-friendly work environment (e.g., health insurance for children and permissions so that employees can receive their children’s report cards) to reduce family strains and, thus, encourage them to give their best at work.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether role conflict in the form of family–work conflict and work–family conflict affects emotional exhaustion, with person–job fit as antecedent. Data were collected from call center workers at banking and insurance firms in the financial services industry in Indonesia. The results of the structural equation model testing showed that the research model was viable. In addition, the hypothesis testing results revealed that person–job fit is negatively related to family–work conflict and work–family conflict. In other words, the more compatible call center workers are with job requirements, the less likely they will experience role conflict (family–work conflict and work–family conflict). Additionally, we found that only family–work conflict is positively related to emotional exhaustion.

Based on our findings, call centers in general and call center managers should consider fostering a family-friendly working environment to prevent role conflict. Moreover, they should assess call center workers’ knowledge, skills, and abilities and include a personality test into their hiring practices to prevent role conflict.

NOTAS AL PIE

- arrow_upward * This article is derived from the project entitled "University internal grant” and has been financed with Universitas Multimedia Nusantara resources.

REFERENCES

- arrow_upward Afsar, B.; Rehman, Z. U. (2017). Relationship between Work-Family Conflict, Job Embeddedness, Workplace Flexibility, and Turnover Intentions. Makara Human Behavior Studies in Asia, v. 21, n. 2, 92-104. https://doi.org/10.7454/mssh.v21i2.3504

- arrow_upward Anderson, J. C.; Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychological Bulletin, v. 103, n. 3, 411-423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- arrow_upward Babakus, E.; Yavas, U.; Ashill, N. J. (2010). Service Worker Burnout and Turnover Intentions: Roles of Person-Job Fit, Servant Leadership, and Customer Orientation. Services Marketing Quarterly, v. 32, n. 1, 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332969.2011.533091

- arrow_upward Bagozzi, R. P.; Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, v. 16, n. 1, 74-94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

- arrow_upward Bakker, A. B. (2013). La teoría de las demandas y los recursos laborales. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, v. 29, n. 3, 107-115. https://doi.org/10.5093/tr2013a16

- arrow_upward Cable, D. M.; DeRue, D. S. (2002). The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, v. 87, n. 5, 875-884. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.875

- arrow_upward Carlson, D. S.; Grzywacz, J. G.; Zivnuska, S. (2009). Is work’family balance more than conflict and enrichment? Human Relations, v. 62, n. 10, 1459-1486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709336500

- arrow_upward Cavazotte, F.; Moreno, V.; Chehab Lasmar, L. C. (2020). Enabling customer satisfaction in call center teams: the role of transformational leadership in the service-profit chain. The Service Industries Journal, v. 40, n. 5-6, 380-393. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2018.1481955

- arrow_upward Chambel, M. J.; Carvalho, V. S.; Cesário, F.; Lopes, S. (2017). The work-to-life conflict mediation between job characteristics and well-being at work. The Career Development International, v. 22, n. 2, 142-164. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-06-2016-0096

- arrow_upward Cho, S. S.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Lim, S.; Jeong, W. C. (2019). Combined Exposure of Emotional Labor and Job Insecurity on Depressive Symptoms Among Female Call-Center Workers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicine, v. 98, n. 12, e14894. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000014894

- arrow_upward CNN Indonesia. (2019). Ibu Kota Pindah, Jakarta Tetap Jadi Pusat Ekonomi. https://www.cnnindonesia.com/ekonomi/20190901135435-532-426552/ibu-kota-pindah-jakarta-tetap-jadi-pusat-ekonomi

- arrow_upward Cyntara, R. (2019). Perlindungan Konsumen Wajib Dilakukan. https://ekbis.harianjogja.com/read/2019/02/22/502/973524/perlindungan-konsumen-wajib-dilakukan

- arrow_upward D’Cruz, P.; Noronha, E. (2008). Doing Emotional Labour: The Experiences of Indian Call Centre Agents. Global Business Review, v. 9, n. 1, 131-147. https://doi.org/10.1177/097215090700900109

- arrow_upward De Cuyper, N.; Castanheira, F.; De Witte, H.; Chambel, M. J. (2014). A multiple‐group analysis of associations between emotional exhaustion and supervisor‐rated individual performance: Temporary versus permanent call‐center workers. Human Resource Management, v. 53, n. 4, 623-633. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21608

- arrow_upward Donovan, D. T.; Brown, T. J.; Mowen, J. C. (2004). Internal Benefits of Service-Worker Customer Orientation: Job Satisfaction, Commitment, and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors. Journal of Marketing, v. 68, n. 1, 128-146. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.1.128.24034

- arrow_upwardDos Anjos Grilo Pinto De Sá, A. C.; Moura E Sá, P. H. F. L. (2014). Job Characteristics and Their Implications on the Satisfaction Levels of call Center Employees: a study on a large telecommunications company. Review of Business Management, v. 16, n. 53, 658-676. https://doi.org/10.7819/rbgn.v16i53.1553

- arrow_upward Ducharme, L. J.; Knudsen, H. K.; Roman, P. M. (2007). Emotional exhaustion and turnover intention in human service occupations: The protective role of coworker support. Sociological Spectrum, v. 28, n. 1, 81-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732170701675268

- arrow_upward Edwards, J. R. (1991). Person-job fit: A conceptual integration, literature review, and methodological critique. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.). International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, v. 6, 283-357

- arrow_upward Edwards, J. R. (1996). An Examination of Competing Versions of the Person-Environment Fit Approach to Stress. The Academy of Management Journal, v. 39, n, 2, 292-339. https://doi.org/10.5465/256782

- arrow_upward Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, v. 18, n. 1, 39-50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- arrow_upward Frone, M. R.; Russell, M.; Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, v. 77, n. 1, 65-78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65

- arrow_upward Geraldes, D.; Madeira, E.; Carvalho, V. S.; Chambel, M. J. (2019). Work-personal life conflict and burnout in contact centers: The moderating role of affective commitment. Personnel Review, v. 48, n. 2, 400-416. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2017-0352

- arrow_upward Glaser, W.; Hecht, T. D. (2013). Work-family conflicts, threat-appraisal, self-efficacy and emotional exhaustion. Journal of Managerial Psychology, v. 28, n. 2, 164-182. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941311300685

- arrow_upward Greenhaus, J. H.; Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of Conflict Between Work and Family Roles. Academy of Management Review, v. 10, n. 1, 76-88. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1985.4277352

- arrow_upward Hair, J. F.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W. (1995). Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings (4th edition). Prentice Hall

- arrow_upward Hair, J. F.; Black, W. C.; Babin, B. J.; Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th Edition). Prentice Hall

- arrow_upward Hudson, S.; González-Gómez, H. V.; Rychalski, A. (2017). Call Centers: Is there an Upside to the Dissatisfied Customer Experience? Journal of Business Strategy, v. 38 n. 1, 39-46. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBS-01-2016-0008

- arrow_upward Igbaria, M.; Zinatelli, N.; Cragg, P.; Cavaye, A. L. M. (1997). Personal Computing Acceptance Factors in Small Firms: A Structural Equation Model. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, v. 21, n. 3, 279-301. https://doi.org/10.2307/249498

- arrow_upward Jawahar, I.M.; Kisamore, J.L.; Stone, T.H.; Rahn, D. L. (2012). Differential Effect of Inter-Role Conflict on Proactive Individual’s Experience of Burnout. Journal of Business and Psychology, v. 27, n. 2, 243-254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9234-5

- arrow_upward Kahn, R. L.; Wolfe, D. M.; Quinn, R. P.; Snoek, J. D.; Rosenthal, R. A. (1964). Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. Sage Publications, Inc

- arrow_upward Karatepe, O. M. (2013). The effects of work overload and work-family conflict on job embeddedness and job performance: The mediation of emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, v. 25, n. 4, 614-634. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111311322952

- arrow_upwardKaratepe, O. M.; Karadas, G. (2016). Service employees’ fit, work-family conflict, and work engagement. Journal of Services Marketing, v. 30, n. 5, 554-566. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-02-2015-0066

- arrow_upward Karatepe, O. M.; Sökmen, A.; Yavas, U.; Babakus, E. (2010). Work-family conflict and burnout in frontline service jobs: Direct, mediating and moderating effects. Ekonomika a Management, n. 4, 61-73. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/WORK-FAMILY-CONFLICT-AND-BURNOUT-IN-FRONTLINE-JOBS%3A-Karatepe-S%C3%B6kmen/45f4cacdb21af1139ad8bbba48c8a7f2736837c7

- arrow_upward Knudsen, H. K.; Ducharme, L. J.; Roman, P. M. (2009). Turnover Intention and Emotional Exhaustion “at the Top”: Adapting the Job Demands-Resources Model to Leaders of Addiction Treatment Organizations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, v. 14, n. 1, 84-95. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013822

- arrow_upward Kristof-Brown, A. L.; Zimmerman, R. D.; Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals' fit at work: a meta‐analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, v. 58, n. 2, 281-342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x

- arrow_upward Maertz, C. P.; Campion, M. A. (2004). Profiles in Quitting: Integrating Process and Content Turnover Theory. Academy of Management Journal, v. 47, n. 4, 566-582. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159602

- arrow_upward Maslach, C.; Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, v. 2, n. 2, 99-113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

- arrow_upward Mengenci, C. (2014). The Mediating Affect of Supervisory Support Between P-O Fit, PJobFit, Stress, Surface Acting and Emotional Exhaustion in Service Sector: Evidence From Turkey. International Journal of Liberal Arts and Social Science, v. 2, 1402-1414. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270645641_The_Mediating_Affect_of_Supervisory_Support_Between_P-O_Fit_PJobFit_Stress_Surface_Acting_and_Emotional_Exhaustion_in_Service_Sector_Evidence_From_Turkey

- arrow_upward Mukherjee, A.; Malhotra, N. (2006). Does role clarity explain employee-perceived service quality? A study of antecedents and consequences in call centres. International Journal of Service Industry Management, v. 17, n. 5, 444-473. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564230610689777

- arrow_upward Mulki, J. P.; Jaramillo, F.; Locander, W. B. (2006). Emotional exhaustion and organizational deviance: Can the right job and a leader’s style make a difference? Journal of Business Research, v. 59, n. 12, 1222-1230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.09.001

- arrow_upward Netemeyer, R. G.; Boles, J. S.; McMurrian, R. (1996). Development and Validation of Work-Family Conflict and Family-Work Conflict Scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, v. 81, n. 4, 400-410. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400

- arrow_upward Otoritas Jasa Keuangan. (2018). Layanan Pengaduan Konsumen di Sektor Jasa Keuangan. https://www.ojk.go.id/id/regulasi/Pages/Layanan-Pengaduan-Konsumen-di-Sektor-Jasa-Keuangan.aspx

- arrow_upward Pasewark, W. R.; Viator, R. E. (2006). Sources of Work‐Family Conflict in the Accounting Profession. Behavioral Research in Accounting, v. 18, n. 1, 147-165. https://doi.org/10.2308/bria.2006.18.1.147

- arrow_upward Porter, M. E.; Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1144-7_16

- arrow_upward Puyod, J. V.; Charoensukmongkol, P. (2019). The contribution of cultural intelligence to the interaction involvement and performance of call center agents in cross-cultural communication. Management Research Review, v. 42, n. 12, 1400-1422. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-10-2018-0386

- arrow_upward Richter, A.; Schraml, K.; Leineweber, C. (2015). Work–family conflict, emotional exhaustion and performance-based self-esteem: Reciprocal relationships. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, v. 88, n. 1, 103-112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-014-0941-x

- arrow_upward Ro, H.; Lee, J. E. (2017). Call center employees’ intent to quit: Examination of job engagement and role clarity. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, v. 18, n. 4, 531-543. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2017.1292163

- arrow_upward Rod, M.; Ashill, N. J. (2013). The impact of call centre stressors on inbound and outbound call- centre agent burnout. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, v. 23, n. 3, 245-264. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604521311312255

- arrow_upward Sawyerr, O. O.; Srinivas, S.; Wang, S. (2009). Call center employee personality factors and service performance. Journal of Services Marketing, v. 23, n. 5, 301-317. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040910973413

- arrow_upward Seery, B. L.; Corrigall, E. A. (2009). Emotional Labor: Links to Work Attitudes and Emotional Exhaustion. Journal of Managerial Psychology, v. 24, n. 8, 797-813. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940910996806

- arrow_upward Shih-Tse Wang, E. (2014). The effects of relationship bonds on emotional exhaustion and turnover intentions in frontline employees. Journal of Services Marketing, v. 28, n. 4, 319-330. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-11-2012-0217

- arrow_upward Unal, Z. M. (2017). The Mediating Role of Meaningful Work on the Relationship Between Needs for Meaning-Based Person-Job Fit and Work-Family Conflict. International Scientific Conference on Sustainable Development Goals-2017, November. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Zeynep_Uenal2/publication/321484500_The_Mediating_Role_of_Meaningful_Work_on_the_Relationship_between_Needs_for_Meaning-based_Person-Job_Fit_and_Work-Family_Conflict/links/5a243440aca2727dd87e4b0f/The-Mediating-Role-of-Meaningful-Work-on-the-Relationship-between-Needs-for-Meaning-based-Person-Job-Fit-and-Work-Family-Conflict.pdf

- arrow_upward Vads. (2017). Contact Center di Industri Keuangan merupakan “Sebuah Kebutuhan Dasar”. https://www.vads.co.id/berita/?cat=Events

- arrow_upward Wiratri, A. (2018). Menilik Ulang Arti Keluarga pada Masyarakat Indonesia. Jurnal Kependudukan Indonesia, v. 13, n. 1, 15-26. https://ejurnal.kependudukan.lipi.go.id/index.php/jki/article/view/305/pdf%20Wiratri,%202018

- arrow_upward Zambas, J. (2018). The 20 Most Stressful Jobs in the World. https://www.careeraddict.com/stressful-jobs

- arrow_upward Zuraya, N. (2017). OJK Optimalkan Peran Lembaga Keuangan Pangkas Ketimpangan. https://www.republika.co.id/berita/ekonomi/keuangan/17/11/22/oztc4m383-ojk-optimalkan-peran-lembaga-keuangan-pangkas-ketimpangan